Contrary to what some believe, Sherry wine isn’t sweet. In fact, most are dry. People in Spain savor Sherry wine like a fine whisky. Get to know the different Sherry wine styles and which ones you should try (and even the ones to avoid).

A Guide to Sherry Wine

Many people mistakenly believe that all Sherry is sweet, sticky, and unpalatable. Maybe it was a childhood sip snuck from a dusty old bottle kept atop grandma’s fridge or a cheap label of the mass-produced California “sherry” on the supermarket shelf.

If you love brown spirits, Sherry might be your new favorite wine!

What is Sherry Wine?

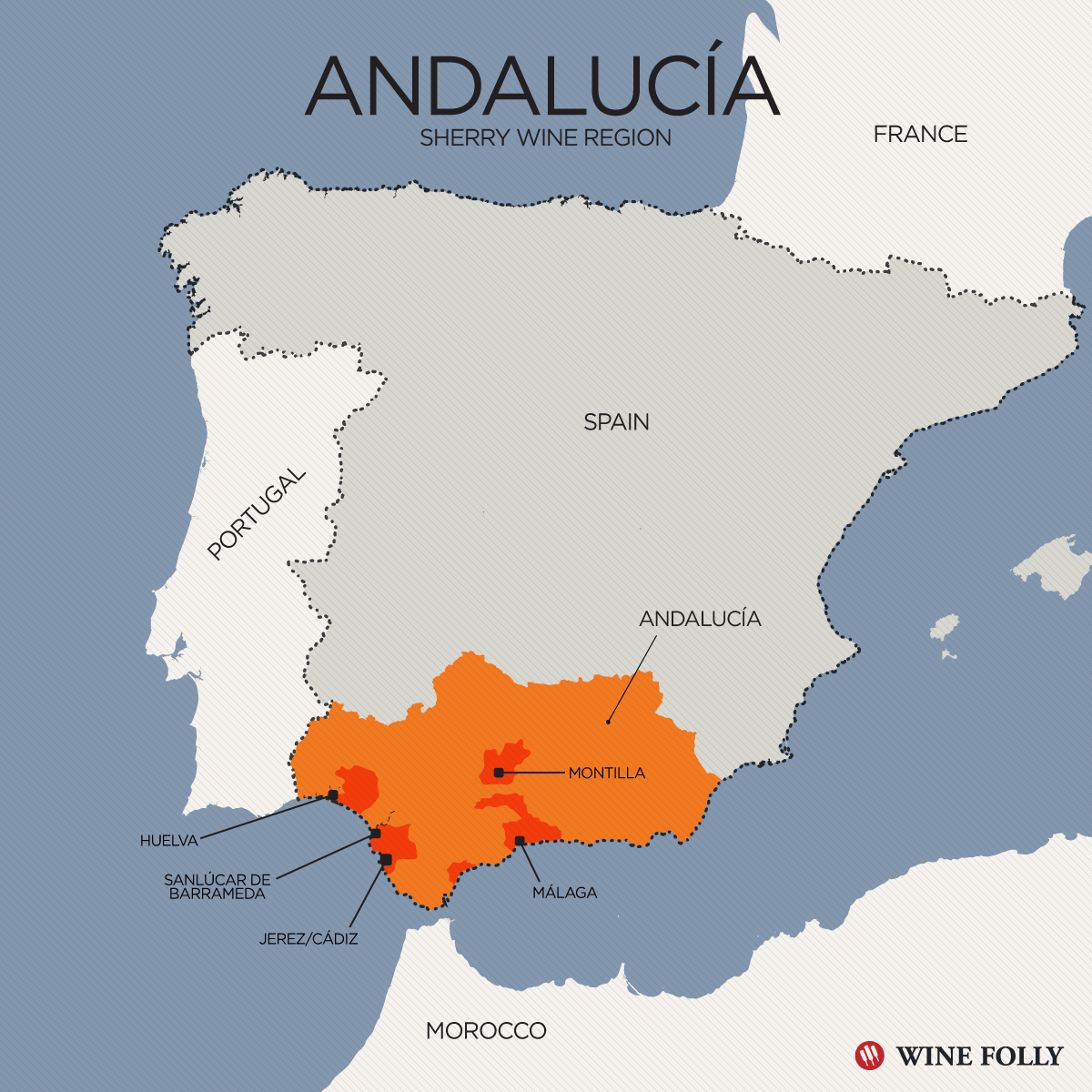

We can start with a few truths: Sherry is a fortified white wine from Andalucía in Southern Spain. Most of it is dry and pairs great with food.

Isn’t Sherry Just a Sweet Wine?

Some sweet styles make great dessert wines or fireside sippers (such as PX). But they don’t represent the full range of Sherry.

In the mid-20th century, Americans (with a thirst for sweet, soda-like beverages) created a market for sweet Sherry. Meanwhile, Spaniards and Brits kept the best dry, complex styles for themselves.

In fact, the dry styles deserve their place alongside the world’s classic wines.

Where Does Sherry Come From?

Sherry’s magnificence comes from the fact that, like Champagne, true Sherry can only be made in one tiny corner of the world. This area, called the Sherry Triangle, includes Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María. The region’s winds, humidity, soils, and seasonal shifts give Sherry its unique character.

Throughout history, imitators tried to replicate Sherry’s salty, nutty, and aromatic profile. However, unlike Champagne, which is strictly protected, the Sherry Consejo Regulador and the Spanish government have taken few actions to protect the Sherry name internationally. So, many cheap imitations are still sold with the name Sherry on the bottle.

Most are bulk wines, which use sweeteners and chemicals to enhance color and flavor.

Isn’t Fortified Wine Too Strong?

Well, you’re supposed to drink less of it! Sherry’s powerful flavor and slightly higher alcohol content mean that a single serving can be about half of a normal six-ounce glass of wine. Sherry ranges from 15% ABV to over 20%.

Many full-bodied red wines like Argentine Malbec and Napa Valley Cabernet clock in at 15-16% alcohol or more, so don’t worry. This extra strength makes it a great food-pairing wine.

Types of Sherry Wine

With this background in mind, here are some tips for buying Sherry and pairing it with food.

Styles of Dry Sherry Wine

- FINO & MANZANILLA: These are the lightest styles of Sherry. They age for as few as two or as many as ten years under a layer of flor. After bottling, they are for immediate consumption. They are delicious with olives, Marcona almonds, and cured meats. With oysters, Fino and Manzanilla Sherry vie with Champagne as the greatest pairing on earth.

Try González-Byass’ classic Tío Pepe Fino for a light, crisp classic. For something more funky, try the single-vineyard Valdespino’s Fino Inocente or Hidalgo’s La Gitana Manzanilla En Rama. These are bottled straight from the cask without filtration. Serve Fino and Manzanilla cold for the best results.

- AMONTILLADO: When a Fino’s layer of flor fades, or the wine is intentionally fortified to a high strength, it begins to oxidize and change character. This is an Amontillado Sherry or, simply put, an aged Fino. These wines retain Fino’s salty bite while developing a darker color and a nuttier, richer finish on the palate. Amontillado Sherry is also a versatile food wine, pairing well with prawns, seafood soup, roast chicken, or a cheese plate.

Try Lustau’s Los Arcos for a rich, stylish classic, or Williams & Humbert’s Jalifa 30-year-old VORS for something intense and unforgettable.

- PALO CORTADO: This is a strange, beautiful, and less common style of Sherry that occurs in certain circumstances when flor yeast dies unexpectedly, and the wine begins to take on oxygen. A Palo Cortado delivers salty character, with a body that feels richer and more intense. Palo Cortado can taste like an Amontillado on the palate but often shows a great balance of richness and delicacy.

Try Valdespino’s Palo Cortado Viejo for something delicious and complex, or Hidalgo’s Wellington 20-year for a showpiece.

- OLOROSO: Oloroso never develops flor. Instead, all the wine’s flavor comes from the interaction of wine and air. Many consider oxidized wine faulty, but when aged for 5 to 25 years, the wine in a Sherry solera develops into a full-bodied, dark, and expressive wine that pairs well with braised beef, bitter chocolate, and blue cheese. Oloroso Sherry is aromatic and spicy, and can be drunk like a finely aged bourbon.

Try González Byass’ Alfonso for an archetypal Oloroso, or Fernando de Castilla’s Antique for something rare and memorable.

There’s no other wine that offers the age and complexity of Sherry for the price.

The Fortified Wine in the Age of Exploration

During the Golden Age of Exploration, sailors carried alcohol on every voyage. Because water often carried disease, they mixed in wine or rum to keep it safe to drink.

Merchants fortified wine with brandy to prevent spoilage during long journeys. British wine merchants, who favored fortified wines, established operations in Jerez de la Frontera and shipped these strengthened wines across the seas.

In 1587, Sir Francis Drake raided the port of Cádiz near Jerez and seized thousands of barrels of Sherry. Back in England, Drake’s haul sparked a craze, creating a devoted market for the wines of Jerez.

Jerez, A Place Apart

No region in the world can make wines like those of Jerez.

It’s not just the white chalky soil and warm sun that make Jerez’s wines exceptional. The Poniente and Levante winds blow across the region, providing the open-air cellars with the right combination of humidity and temperature to gently age the wines in barrel.

Because of Andalusia’s warm seaside climate, a unique phenomenon called flor occurs. Each year, a layer of yeast forms on new wine and transforms its flavors. Flor transforms the wine, giving a tangy, salty character as it matures, which is what Sherry is all about.

The Wine Blender’s Art

Like most Champagnes and Scotch, Sherry is a blend. First, winemakers refresh old barrels each year with slightly younger wine. Then, the oldest barrel blends go into bottle.

This is the Solera system, which creates a wine from as few as three or as many as 100 vintages. A Solera is, put simply, a group of barrels used to age a single wine, and the wine in these barrels will develop more complexity each year as fresh wine is added.

Sherry and Spirits

Oak casks are ideal vessels for aging both wine and spirits. Once the Sherry cellar is finished with a cask, it’s sold to a Scotch distiller.

Distillers finish many Scotch Whiskies in used Sherry casks, lending that layer of nutty, toffee-glazed complexity. Macallan, Glenmorangie, and many of the other great Speyside distilleries base their styles on this practice.

Sherry — especially a dark, rich Oloroso or a tangy Amontillado — can be just as intense as an aged whisky. However, Sherry holds great value. For example, spirits with 10 to 20 years of age command a high price, but many Sherries fall under the $25 mark. Many are from Soleras, where the youngest barrel is 10 years old, and the oldest may be 100!